[Emulate] SystemC Communication Ports

- SystemC Communication Ports

SystemC Communication Ports1

Communication: The Need for Ports

There are two concerns: safety and ease of use.

Safety is a concern because all activity occurs within processes, and care must be taken when communicating between processes to avoid race conditions. Events and channels are used to handle this concern.

Ease of use is more difficult to address. SystemC takes an approach that lets modules use channels inserted between the communicating modules with ports. A port is a pointer to a channel outside the module.

This separation of access is managed using a concept known as an interface, which is described in the next section.

Interfaces: C++ and SystemC

An abstract class is a class that is never used directly, but it is used only via derived subclasses. Partly to enforce this concept, abstract classes usually contain pure virtual functions. Pure virtual functions are not allowed to provide an implementation in the abstract class where they are defined as pure.

Pure virtual functions are identified by

- the keyword virtual

- the =0;

class my_interface {

public:

virtual void write(unsigned addr, int data) = 0;

virtual int read(unsigned addr) = 0;

};

You can think of an interface as the application programming interface (API) to a set of derived classes.

DEFINITION: A SystemC interface is an abstract class that inherits from

sc_interfaceand provides only pure virtual declarations of methods referenced by SystemC channels and ports. No implementations or data are provided in a SystemC interface.DEFINITION: A SystemC channel is a class that inherits from either

sc_channelor fromsc_prim_channel, and the channel should inherit and implement one or more SystemC interface classes. A channel implements all the pure virtual methods of the inherited interface classes.

Simple SystemC Port Declarations

DEFINITION A SystemC port is a class templated with and inheriting from a SystemC interface. Ports allow access of channels across module boundaries.

SystemC ports are always defined within the module class definition.

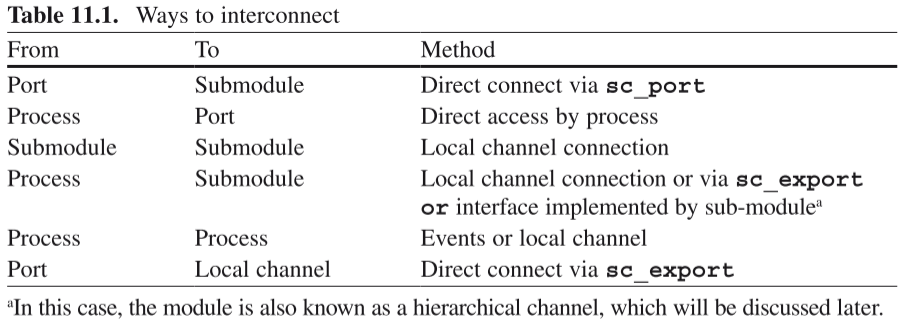

Many Ways to Connect

Port Connection Mechanics

There are two syntaxes for connecting ports: by name and by position.

mod_inst.portname(channel_instance); // Named

mod_instance(channel_instance,…); // Positional

Interconnect example

//FILE: Rgb2YCrCb.h

SC_MODULE(Rgb2YCrCb) {

sc_port<sc_fifo_in_if<RGB_frame> > rgb_pi;

sc_port<sc_fifo_out_if<YCRCB_frame> > ycrcb_po;

};

//FILE: YCRCB_Mixer.h

SC_MODULE(YCRCB_Mixer) {

sc_port<sc_fifo_in_if<float> > K_pi;

sc_port<sc_fifo_in_if<YCRCB_frame> > a_pi, b_pi;

sc_port<sc_fifo_out_if<YCRCB_frame> > y_po;

};

//FILE: VIDEO_Mixer.h

SC_MODULE(VIDEO_Mixer) {

// ports

sc_port<sc_fifo_in_if<YCRCB_frame> > dvd_pi;

sc_port<sc_fifo_out_if<YCRCB_frame> > video_po;

c_port<sc_fifo_in_if<MIXER_ctrl> > control;

sc_port<sc_fifo_out_if<MIXER_state> > status;

// local channels

sc_fifo<float> K;

sc_fifo<RGB_frame> rgb_graphics;

sc_fifo<YCRCB_frame> ycrcb_graphics;

// local modules

Rgb2YCrCb Rgb2YCrCb_i;

YCRCB_Mixer YCRCB_Mixer_i;

// constructor

VIDEO_Mixer(sc_module_name nm);

void Mixer_thread();

};

Local modules communicated via local channels.

// Example of port interconnect by name

SC_HAS_PROCESS(VIDEO_Mixer);

VIDEO_Mixer::VIDEO_Mixer(sc_module_name nm)

: sc_module(nm)

, Rgb2YCrCb_i(“Rgb2YCrCb_i”)

, YCRCB_Mixer_i(“YCRCB_Mixer_i”)

{

// Connect

Rgb2YCrCb_i.rgb_pi(rgb_graphics);

Rgb2YCrCb_i.ycrcb_po(ycrcb_graphics);

YCRCB_Mixer_i.K_pi(K);

YCRCB_Mixer_i.a_pi(dvd_pi);

YCRCB_Mixer_i.b_pi(ycrcb_graphics);

YCRCB_Mixer_i.y_po(video_po);

}

Although slightly more code than the positional notation, the named port syntax is more robust, and tools exist to reduce the typing tedium.

// Example of port interconnect by position

SC_HAS_PROCESS(VIDEO_Mixer);

VIDEO_Mixer::VIDEO_Mixer(sc_module_name nm)

: sc_module(nm)

{

// Instantiate

Rgb2YCrCb_iptr = new Rgb2YCrCb( "Rgb2YCrCb_i");

YCRCB_Mixer_iptr = new YCRCB_Mixer( "YCRCB_Mixer_i");

// Connect

(*Rgb2YCrCb_iptr)( rgb_graphics

,ycrcb_graphics);

(*YCRCB_Mixer_iptr)( K

,dvd_pi

,ycrcb_graphics

,video_po);

}

The problem with positional connectivity is that of keeping the ordering correct. we recommend avoiding the positional syntax entirely, and always using a named port approach.

Accessing Ports From Within a Process

Using the operator-> when accessing ports.

void VIDEO_Mixer::Mixer_thread() {

…

switch (control->read()) {

case MOVIE: K.write(0.0f); break;

case MENU: K.write(1.0f); break;

case FADE: K.write(0.5f); break;

default: status->write(ERROR); break;

}

…

}

Ports feel and behave as if they were pointers.

The SystemC Port Array and Port Policy

The sc_port<T> provides additional template parameters we have not yet discussed: the array size parameter and the port policy parameter.

sc_port<interface[,N[,POL]]> portname;

// N=0..MAX Default N=1

// POL is of type sc_port_policy

// POL defaults to SC_ONE_OR_MORE_BOUND

POL

POL is of type sc_port_policy and it is an enumerated type and has three legal values:

- SC_ONE_OR_MORE_BOUND

- SC_ZERO_OR_MORE_BOUND

- SC_ALL_BOUND

The value of POL enables different checking regarding the connectivity to the port.

SC_ALL_BOUND requires that there are N and only N channels connected to the port

N

$N$ indicates the number of channels to be connected to the port. When $N = 0$, we have a special case that allows an almost unlimited number of ports. In other words, you may connect any number of channels to the port.

Example of sc_port<T> array connectivity

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/SingularityKChen/PicUpload/master/img/20200720163109.png" alt="Example of sc_port

//FILE: Switch.h

SC_MODULE(Switch) {

sc_port<sc_fifo_in_if<int>

,5

,SC_ONE_OR_MORE_BOUND

> T1_ip;

sc_port<sc_signal_inout_if<bool>

,0

> request_op;

...

};

//FILE: Board.h

#include "Switch.h"

SC_MODULE(Board) {

Switch switch_i;

sc_fifo<int> t1A, t1B, t1C, t1D;

sc_signal< bool> request[9];

SC_CTOR(Board): switch_i("switch_i")

{

// Connect 4 T1 channels to the switch

switch_i.T1_ip(t1A);

switch_i.T1_ip(t1B);

switch_i.T1_ip(t1C);

switch_i.T1_ip(t1D);

// Connect 9 request channels to the

// switch request output ports

for (unsigned i=0;i!=9;i++) {

switch_i.request_op(request[i]);

}//endfor

...

}//end constructor

...

};

This class also provides a method, size(), that may be used to examine the declared port size. This method is useful for situations where the array bounds are unknown (i.e., $N = 0$ or using SC_ONE_OR_MORE_BOUND or SC_ZERO_OR_MORE_BOUND ).

//FILE: Switch.cpp

void Switch::switch_thread() {

// Initialize requests

for (unsigned i=0;i!=request_op.size();i++) {

request_op[i]->write(true);

}//endfor

// Startup after first port is activated

wait(T1_ip[0]->data_written_event()

|T1_ip[1]->data_written_event()

|T1_ip[2]->data_written_event()

|T1_ip[3]->data_written_event()

);

while(true) {

for (unsigned i=0;i!=T1_ip.size();i++) {

// Process each port...

int value = T1_ip[i]->read();

}//endfor

}//endwhile

}//end Switch::switch_thread

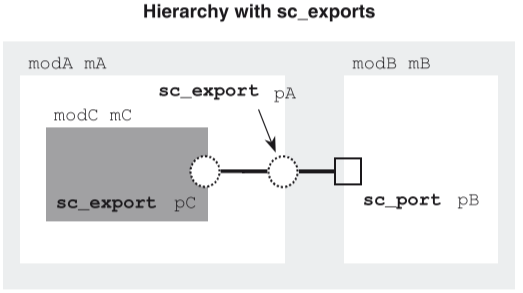

SystemC Exports

The concept of the export

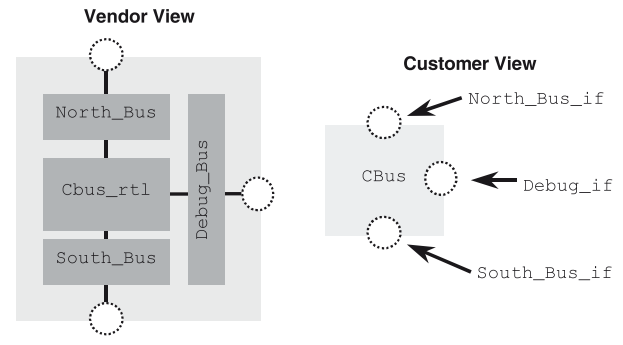

The idea of an sc_export<T> is to move the channel inside the defining module, thus hiding some of the connectivity details and using the port externally as though it were a channel.

Why need the export

For an IP provider, it may be desirable to export only specific channels and keep everything else private. Thus, sc_export<T> allows control over the interface. A hidden interface has the benefit of making the channel simpler to read and understand in the module where the IP is instantiated.

Another reason for using sc_export<T> is to provide multiple interfaces at the top level.

Another reason for using sc_export<T> is communications efficiency down the SystemC hierarchy.

Another powerful possibility with sc_export<T> is to let interfaces be passed up the design hierarchy.

Example of export

// Example of simple sc_export declaration

SC_MODULE(clock_gen) {

sc_export<sc_signal<bool>> clock_xp;

sc_signal<bool> oscillator;

SC_CTOR(clock_gen) {

SC_METHOD(clock_method);

clock_xp(oscillator);

// connect sc_signal channel

// to export clock_xp

oscillator.write(false);

}

void clock_method() {

oscillator.write(!oscillator.read());

next_trigger(10,SC_NS);

}

};

// Example of simple sc_export instantiation

#include "clock_gen.h"

…

clock_gen clock_gen_i(“clock_gen_i”);

collision_detector cd_i(“cd_i”);

// Connect clock

cd_i.clock(clock_gen_i.clock_xp);

…

Connectivity Revisited

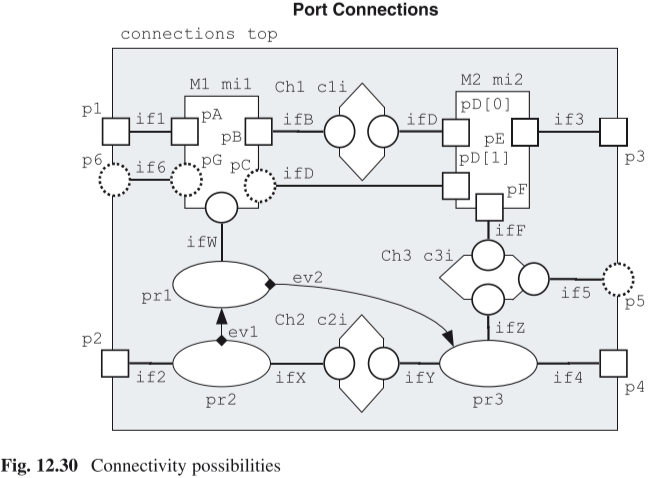

This figure is a handy reference when reviewing the SystemC connection rules, which are listed below:

- A process may communicate with another process in the same module using a channel. For example, process pr2 to process pr3 via interface ifX on channel c2i.

- A process may communicate with another process in the same module using an event to synchronize exchanges of information through data variables instantiated at the module level (e.g., within the module class definition). For example, process pr2 to process pr1 via event ev1.

- A process may communicate with a process upwards in the design hierarchy using the interfaces accessed via

sc_port<T>. For example, process pr3 via port p4 using interface if4. - A process may communicate with processes in submodule instances via interfaces to channels connected to the submodule ports. For example, process pr3 to module mi2 via interface ifZ on channel c3i.

- An

sc_export<T>may connect to anothersc_export<T>via interfaces to local channels. For example, port p5 to channel c3i using interface if5. - An

sc_port<T>may connect directly to ansc_port<T>of submodules. For example, port p1 is connected to port pA of submodule mi1. - An

sc_export<T>may connect directly to ansc_export<T>of a submodule. For example, port p6 is directly connected to port pG of submodule mi1. - An

sc_port<T>may connect indirectly to a process by letting the process access the interface. This is just a process accessing a port described previously. For example, process pr1 communicates with submodule mi1 through interface ifW. - An

sc_port<T,N>array may be used to create multiple ports using the same interface. For example, $pD[0]$ and $pD[1]$ of submodule mi2.

-

D. C. Black, J. Donovan, B. Bunton, and A. Keist, SystemC: From the Ground Up, Second Edition, 2nd ed. Springer US, 2010. ↩